December 2025

Process Optimization

Sizing pressure relief piping systems: Dual isenthalpic-isentropic flow

Vapor and two-phase flows in pressure relief discharge piping are characterized by rapid variations in velocity, density and temperature, particularly in systems involving rupture disks and short piping lengths. Traditional flow modeling approaches often rely on isenthalpic assumptions, which can oversimplify the complex thermodynamic behavior of such systems and lead to less accurate predictions. This article proposes an improved method that integrates both isenthalpic and isentropic flow analyses to more accurately capture the thermodynamic and fluid dynamic conditions within relief systems. By explicitly accounting for temperature variations, the method enables more precise calculation of key flow properties such as velocity, density and temperature. A comparative analysis using a short rupture disk piping configuration demonstrates that the dual-flow approach significantly enhances the accuracy and reliability of pressure relief system design. The integrated method thus provides a more robust and dependable tool for engineers, particularly in applications involving rapid thermodynamic transitions and non-ideal behavior.

Temperature changes in compressible pipe flow. In pressure relief systems, accurately estimating temperature changes during fluid flow is vital for relief piping sizing. Fluid velocity changes and the Joule-Thomson effect (affecting non-ideal vapors) can cause temperature variations. Choked flow conditions often lead to the lowest temperatures. While industry sizing methods (isothermal, adiabatic, isenthalpic and isentropic) can be helpful, they may not always precisely represent the actual temperature changes experienced in the system.

Isothermal pipe flow. Isothermal pipe flow analysis simplifies fluid dynamics calculations by assuming a constant fluid temperature. API 521 often recommends this approach for its conservative results.1 It is applicable to ideal gases, and also to real gases when the compressibility factor remains relatively constant. However, this method does not account for the Joule-Thomson effect and changes in kinetic energy. Therefore, isothermal pipe flow is classified as a non-adiabatic and non-isentropic process.

Adiabatic pipe flow. Adiabatic pipe flow, which assumes no heat transfer, is a widely used method for calculating compressible gas flow because it yields more accurate results than isothermal flow. The equation for adiabatic flow is complex due to the temperature changes that occur. While adiabatic flow is suitable for ideal gases and real gases with nearly constant compressibility factors, it does not account for the Joule-Thomson effect.

Isenthalpic pipe flow. The Omega method, a two-point data method, is commonly used for two-phase calculations. It typically assumes an isenthalpic thermodynamic path (constant enthalpy). The pressure and specific volume correlations are derived from isenthalpic flash calculations. This method accurately accounts for the Joule-Thomson effect and compressibility factor changes, making it suitable for non-ideal vapors, especially those with smaller ideal gas-specific capacity ratios. Because the isenthalpic path does not account for kinetic energy changes, it tends to underpredict mass flowrates in piping systems.

Isentropic pipe flow. Isentropic flow—while accounting for Joule-Thomson effect, kinetic energy changes and compressibility factor changes—is unsuitable for real pipe flow due to irreversible friction. The pressure and specific volume correlations are derived from isentropic flash calculations. Isentropic flow tends to overestimate mass flowrate because it assumes a frictionless, ideal process, neglecting the energy lost to friction in real-pipe systems. Actual pipe flow conditions in relief systems typically fall between isenthalpic and isentropic, and while isentropic flow is suitable for frictionless nozzles, it is often inaccurately applied to real-pipe systems with friction.

Dual isenthalpic-isentropic pipe flow. To accurately size relief piping systems for both vapor and two-phase flow, it is crucial to consider fluid property changes throughout the relief system, including temperature and compressibility factor. The dual isenthalpic-isentropic pipe flow model provides a more accurate analysis of frictional pipe flow than either isenthalpic or isentropic flow alone, particularly when accounting for the Joule-Thomson effect and changes in kinetic energy. This model employs isenthalpic and isentropic flash calculations to determine pressure and specific volume correlations, accounting for actual flow conditions. This model assumes ideal, frictionless pipes undergo isentropic flow, while frictional pipes experience isenthalpic flow.

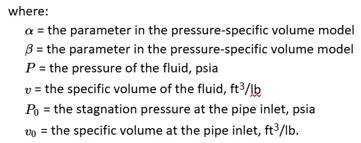

Simpson’s equation (Eq. 1) is among the most accurate models for correlating pressure with specific volume:2

![]()

The two parameters in Eq. 1 are determined using Eq. 2 for β𝛽 and Eq. 3 for αα:

Basic equations for pipe flow. Eq. 6 is a fundamental pipe flow equation applicable to compressible flow, including both vapor and two-phase conditions:

![]()

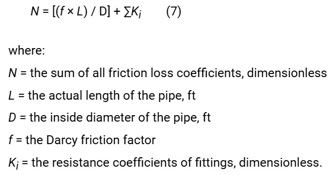

For a fully turbulent relief system, the sum of all friction loss coefficients (N) is introduced to simplify pipe flow calculations. N is independent of the Reynolds number (Eq. 7):

The total pressure drop in Eq. 6 consists of three components: friction loss, kinetic energy change and elevation change, as expressed in Eq. 8:

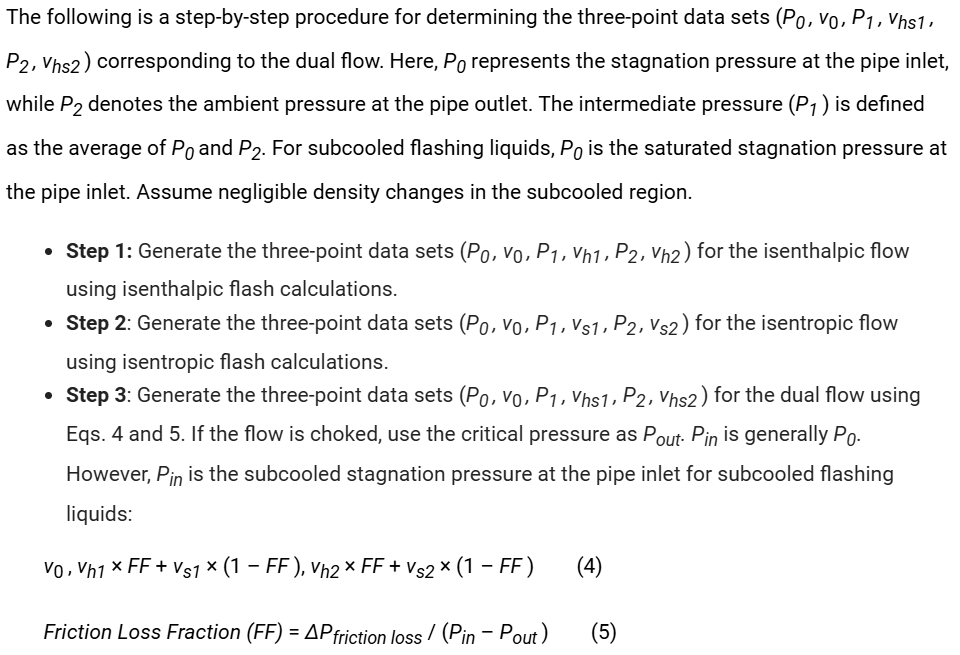

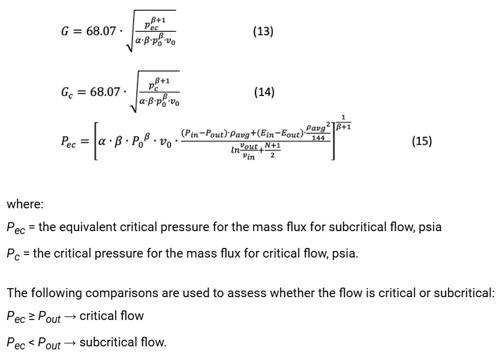

Equations for dual isenthalpic-isentropic pipe flow. The mass flux in a relief piping system equipped with a rupture disk, from vessel stagnation pressure to pipe outlet pressure, is calculated using Eqs. 13–15. These equations are derived from the pressure relief valve (PRV) sizing equation developed by Kim, et al.3 The equations are intended to determine the mass flux based on known vessel stagnation conditions, the relief piping configuration and the ambient pressure at the pipe outlet. The equations are valid for pipes with a constant diameter. When dealing with multiple pipe sections of different diameters, the equations can be applied individually to each section, although this approach requires considerable additional effort. Converting the system to a single equivalent diameter is the preferred approach. However, it is crucial to check for choked flow at the points where diameter changes occur.

In Eq. 15, 1 in N+1 represents the kinetic energy change resulting from a stagnant state in the vessel to moving within the pipe. It accounts for the increase in kinetic energy as the fluid accelerates from zero velocity to a non-zero velocity within the pipe. Instead of analyzing them together, the entrance and pipe sections can be analyzed separately with focused attention on each. Pin is generally P0. However, Pin is the subcooled stagnation pressure at the pipe inlet for subcooled flashing liquids.

If Pec < Pout, the flow is subcritical. In this case, Pec, the equivalent critical pressure corresponding to the mass flux, is calculated directly—no iteration is required. If Pec > Pout, the flow is critical. In this case, the calculation of Pec must be repeated iteratively, using the newly calculated Pec in place of Pout in each subsequent iteration. This process continues until Pec becomes nearly equal to Pout. At convergence, Pec is taken as the critical pressure, Pc. For subcooled flashing liquids, the simple liquid flow equation should be used when the Pec is greater than P0, indicating that flashing is not anticipated along the pipe flow path. The flow is choked when the flow pressure drops to the saturated pressure (P0).

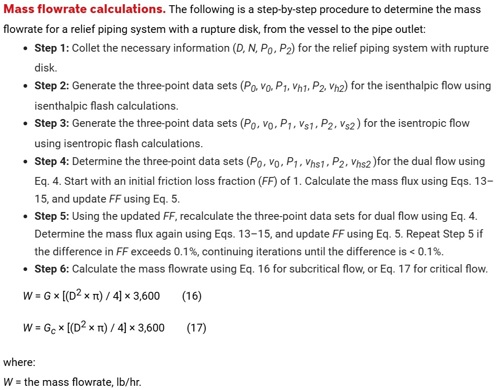

Validation of dual flow. To validate dual flow, the flow capacity of a rupture disk and piping system (with constant pipe diameter) can be evaluated using the example in API 520 Part I, Annex E.4 Calculating the mass flowrate using established methods and comparing results verifies dual flow capacity. In this example, the following data is provided.

- The molecular weight of the fluid: 20 (assumed a mixture of 33.25 mol% hydrogen and 66.75 mol% air)

- Vapor compressibility factor: 1

- Ideal gas specific heat ratio: 1.4

- Pressure in the vessel, P0: 124.7 psia

- Temperature in the vessel: 200°F (93.3°C)

- Backpressure, P2: 14.7 psia.

- Three-point data sets from isenthalpic flash calculations: 124.7 psia, 2.842718 ft3/lb; 69.7 psia, 5.078256 ft3/lb; 14.7 psia, 24.042796 ft3/lb

- Three-point data sets from isentropic flash calculations: 124.7 psia, 2.842718 ft3/lb; 69.7 psia, 4.290722 ft3/lb; 14.7 psia, 12.867032 ft3/lb.

TABLE 1 summarizes the specifications of the overall piping system. While the total system N for compressible flow generally excludes pipe exit loss, API 520 includes it in the Crane method, albeit with a note that is not applicable to the specific method.4

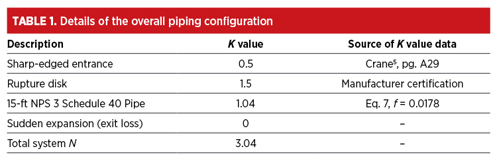

The dual flow, as shown in TABLE 2, accurately predicts mass flowrate in compressible flow applications, aligning with the industry standard adiabatic vapor flow equation.

This accuracy is further supported by research, such as that by Kim, et al., on the uncertainty of the average density in the adiabatic vapor flow equation, which highlights that a lower average density could lead to slightly lower critical pressure and mass flowrate compared to the dual flow.6 However, the dual flow also demonstrates deviations from idealized isenthalpic and isentropic flows, which are expected because actual pipe flow conditions are not truly isenthalpic nor isentropic. Dual flow conditions are intermediate between isenthalpic and isentropic flows since the calculated FF is 0.517. When designing pressure relief systems, especially those incorporating rupture disks, a derating factor of 0.9 should be applied to the calculated mass flowrate. This factor accounts for uncertainties in the flow resistance method and is required by applicable codes to ensure adequate safety and prevent overpressure.

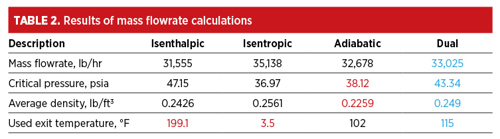

How to estimate fluid temperature. The exit temperature of a fluid in a pipe flow can be calculated by considering the reduction in enthalpy due to the change in kinetic energy at the pipe's exit pressure. As the fluid flows through the pipe, its velocity can change, which leads to a change in kinetic energy. Both the Joule-Thomson effect and kinetic energy changes can influence the fluid temperature in a pipe.

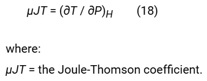

The Joule-Thomson effect is purely due to deviation from ideality. Therefore, any ideal gas has no Joule-Thomson effect. For example, the decrease of temperature at the pipe exit due to the Joule-Thomson effect is around 1°F (Eq. 18).

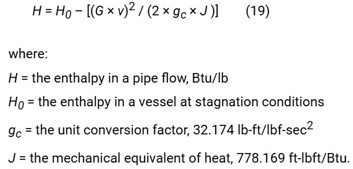

The reduction in enthalpy due to the change in kinetic energy is obtained using Eq. 19. The specific volume can be based on pressure and specific volume correlations for dual flow. The temperature of a fluid in a pipe flow can be calculated at the reduced enthalpy and the pressure in a pipe for known mass flux.

For the example, temperature changes within the piping are plotted in FIG. 1. In isenthalpic flow (HF, constant enthalpy), no temperature change occurs because enthalpy is directly related to temperature for nearly ideal gases, and negligible Joule-Thomson effect applies. Conversely, in isentropic flow (SF, constant entropy), temperature decreases as kinetic energy increases, and again, there is negligible Joule-Thomson effect for nearly ideal gases. In dual isenthalpic-isentropic flow (Dual), the temperature change is limited by the isentropic flow. Friction losses do not increase kinetic energy, leading to a smaller enthalpy decrease than in pure isentropic flow. The dual flow's temperature changes closely match the calculated values, suggesting the flow effectively mimics both isenthalpic and isentropic behaviors. This indicates a successful blend of the two thermodynamic processes. However, individual isenthalpic and isentropic flows show significant deviations from the calculated values.

Takeaways. The proposed method integrates both isentropic and isenthalpic flows to offer a more comprehensive representation of pipe flow conditions, particularly in systems involving rupture disks and short piping. By considering both thermodynamic flow paths, it delivers a more accurate depiction of the flow behavior within the piping system. A comparison of the new method with traditional methods in a short rupture disk piping system demonstrates that the dual flow approach significantly enhances the reliability of pressure relief system design and analysis. This method is applicable to vapor, two-phase and subcooled flashing liquids to determine the mass flowrate for known upstream and downstream pressures.

Essentially, the new method offers a more precise and dependable tool for sizing and designing pressure relief systems, especially when dealing with rapid changes in velocity, density and significant temperature variations. Furthermore, the dual flow approach offers a method for accurately predicting fluid temperatures within a pipe.

This article has presented a dual flow approach to pipe flow calculations, moving from stagnation pressure in a vessel to the pipeline exit (forward calculations). This approach, which can also be adapted for backward calculations, will soon be extended to determine relief valve backpressure on PRVs. Forward pressure drop calculations for PRV inlet piping, using a specified pipe size and a known mass flux, will also be included.

LITERATURE CITED

- American Petroleum Institute (API) Standard 521, “Pressure-relieving and depressuring systems,” 7th Ed., June 2020.

- Simpson, L. L., “Navigating the two-phase maze,” International Symposium on Runaway Reactions and Pressure Relief Design, Boston, Massachusetts, August 2–4,1995.

- Kim, J. S., et al., “Use a simple vapor equation for sizing two-phase pressure relief valves,” Hydrocarbon Processing, July 2022.

- API, “Sizing, selection and installation of pressure-relieving devices, Part I-sizing and selection,” API Standard 520, Part I, 10th Ed., October 2020.

- Crane Technical Paper No. 410, “Flow of fluids through valves, fittings and pipe,” Crane Co., 1982.

- Kim, J. S., et al., “A novel adiabatic pipe flow equation for ideal gases,” Journal of Fluids Engineering, January 2012.

Comments